Architecture, Texture, and Grace: A Cover Image Story

Hello Milkweed readers! I’m Mary Austin Speaker, Milkweed’s Creative Director, and I was honored to talk with Ama Codjoe this week about her extraordinary first book, Bluest Nude, which is due out in September 2022.

Mary Austin Speaker: Bluest Nude is a powerful, vulnerable collection of poems that explores the practice of seeing and being seen as well as the ways we move through intimacy, memory, and art. Can you describe some of the central experiences that inspired Bluest Nude?

Ama Codjoe: In 2019, I attended the art exhibit, Posing Modernity: the Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, curated by Denise Murrell at the Wallach Art Gallery in Harlem, New York. Afterwards, I read every page of Murrell’s exhibition book which led me to other images and texts including Lorraine O’Grady’s “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity.” I began to think and write through questions such as: What is the role of art-making in constructing subjectivity? What perpetual challenges arise when depicting the black feminine nude? Are there ways to circumvent, embrace, wrestle, or dance with them? I tasked myself with creating “paintings” of that figure moving through the intimacies and solitudes of her life.

MAS: You bring many artists into the pages of Bluest Nude. What made you choose the artists and artworks addressed?

AC: The artists and artworks in Bluest Nude are a part of my everyday life: they are the paintings, like Matisse’s Bathers with a Turtle that almost bind me in place as I stand before them; they are overheard snippets of the artistic process, like those from the painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and the photographer Deana Lawson; and they are provocative pieces I’ve returned to again and again, like Betye Saar’s The Liberation of Aunt Jemima. Bluest Nude also includes poems inspired by the choreographers Trisha Brown and Pina Bausch. Because these works and their images are deeply felt, they have become a part of my psyche, and they often emerge in my writing practice. In other words, the artwork chooses me.

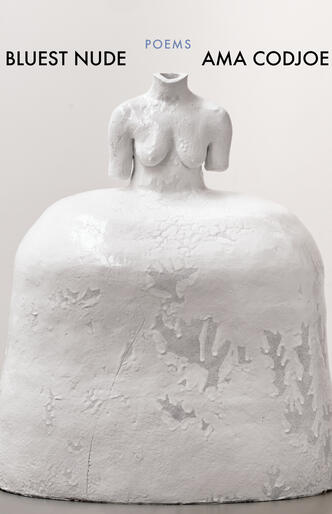

MAS: Why did you choose Simone Leigh’s artwork for the cover image? How do you think Martinique enters into conversation with your poems?

AC: Simone Leigh is a phenomenon. The scale of her work, by which I mean its size, ambition, and resonance, is awe-inspiring. I considered a few images of Leigh’s sculptures, but Martinique was best able to hold and expand the many notes of the book’s title as well as provide—through its architecture, texture, and grace—an open doorway for the reader to enter. Additionally, a two-dimensional image of a three-dimensional sculpture, especially one like Martinique, seems to speak to the qualities and impossibilities of translation inherent in the poetic act. For these reasons, I have started to think of Martinique as the last poem of the book. Or, for sighted readers, the first poem—the first image they see. As a longtime admirer of Leigh’s work, I feel thrilled and humbled to have an image of Martinique on the cover of Bluest Nude. It’s truly a dream come true.

Mary, as the designer and acquiring editor, I’m wondering if you have any thoughts to add. What struck you about the image and its relationship to Bluest Nude?

MAS: One of the elements that drew me to Bluest Nude was the way it dives deep into the double-bind so many people inhabit—the seeming impossibility of authentic representation, of authentic self-representation. To me, Martinique combines the drama of the spellbinding female costume with the violence of erasure (and also reminds me of the poems in the book in which you refuse to name crucial events). I see why you would consider the image something like the last poem in the book. Poetry and visual art both have the capacity to pose questions without answers, to offer a mood without trying to resolve it. In this way the reader or audience is invited to fill in the blank, as it were. Can you tell me more about your relationship to uncertainty, inconclusiveness or mystery?

AC: In much of my life, I am a planner: I relish paper calendars and crisp agendas. As a poet, I thrive on uncertainty and delight in mystery. In poems I love most, it’s this quality that makes me return to them again and again. It also makes me hesitant to discuss my interpretation of the poems I’ve written. In doing so, I often feel like I’m robbing the reader of their own experience. So much of what I bring to the poem: the questions, research, or life experiences is not, finally, evidenced in the poem itself; it’s both there and not there.

MAS: Another thing that made Bluest Nude stand out to me is the way you engage with themes of nakedness and shame. I’m curious if you identify modes of self-perception with particular cultures and, if so, to what extent these differences work their way into the poems of Bluest Nude?

AC: In Ways of Seeing the art critic John Berger distinguishes being naked (nakedness) from being seen as naked (nudity) which is useful to a point, but I wanted the speakers of Bluest Nude to move through many different cultures, realities, and rooms. For example, a bare-breasted speaker in Ghana or the Congo resides differently in their context, with its particular customs, norms, and social dynamics, than a topless woman in the United States. I also write about completely imagined spaces such as an afterlife where the speaker communes with naked women, among them the poets Wanda Coleman and Gwendolyn Brooks. By utilizing different ways of seeing our seeing, I hope—through the craft of poetry—to discover or create spaces of liberation and connection for the speakers in addition to recognizing the social power, oppression, and shame inherent in the gaze of others and ourselves. Put another way, it makes a difference who is doing the looking. Ultimately, I’m interested in what a loving gaze, full of intelligence, history, joy, and pain, can bring to the body.