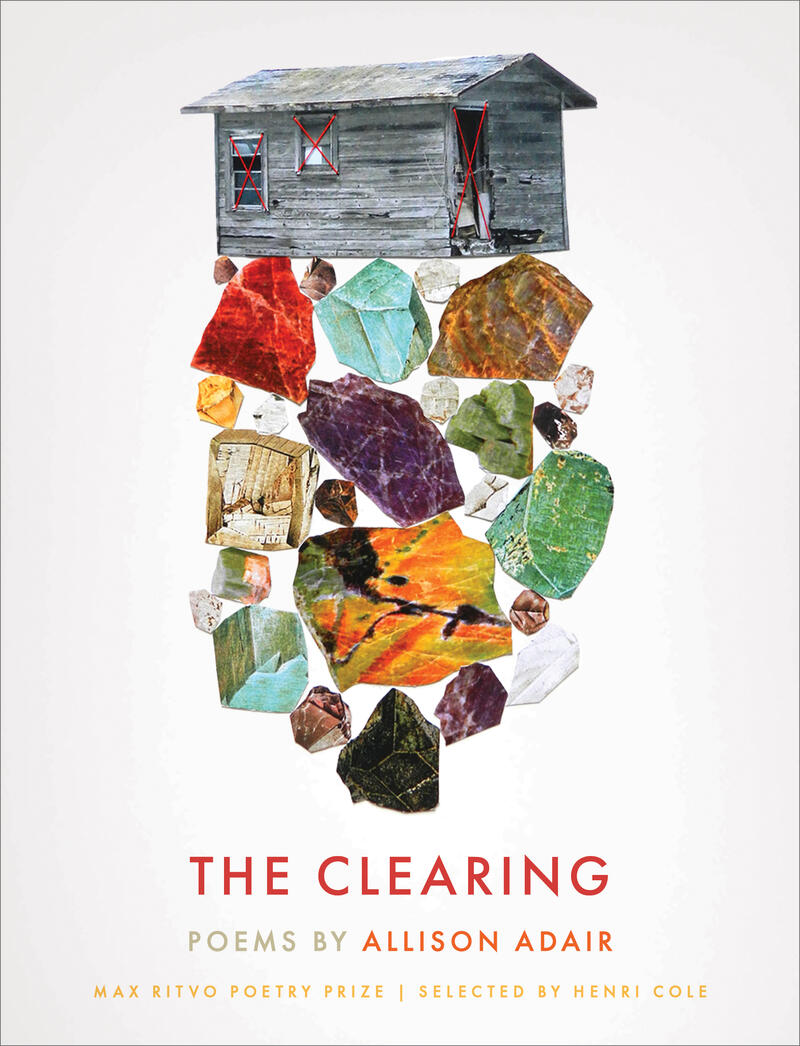

Deep Cuts—Allison Adair's The Clearing

Hello, friends, and welcome to another edition of Deep Cuts. In this series, we’ll be diving in with some of our authors and discussing the behind-the-scenes work that goes into the composition and production of their books. This time around, I am beyond thrilled to be in conversation with the winner of the 2020 Max Ritvo Poetry Prize, Allison Adair.

Her recently-released poetry collection, The Clearing, is a hypnotic exercise in tangible language that verbs us through reflections on motherhood, on imagination, on desire, on flora and fauna, and more. Her poems ask readers to consider how close language can get to the material it’s meant to represent; for Adair, the answer seems to be—well, why don’t I let her talk about it, instead? Read on to learn more!

Bailey Hutchinson: Something (among many things) I celebrate about your poetry is its verdancy—every poem reads like a teeming garden, ripe with color. Even more, this richness doesn’t just hold delight, which I think is what we typically associate with such language—it also holds melancholy, loss. How do you manage that?

Allison Adair: In high school our hippie English teacher assigned Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Many of us rolled our eyes at Annie Dillard’s obsession with the natural world, which felt, in our building surrounded by farms and forests, redundant, the very thing penning us in. There were endless jokes about the word “fecundity.” But what Dillard said stuck with me: “I don’t know what it is about fecundity that so appalls. I suppose it is the teeming evidence that birth and growth, which we value, are ubiquitous and blind, that life itself is so astonishingly cheap, that nature is as careless as it is bountiful, and that with extravagance goes a crushing waste that will one day include our own cheap lives […]. Every glistening egg is a memento mori.” You can imagine why sixteen-year-olds would reject this. But the teacher was seeding us with ideas that would bear fruit years later. Poetry owes a debt to beauty, especially natural beauty. But beauty comes at a cost: to free its pollen, a perfect seed pod must dehisce; canopy branches knit together until the undergrowth ferments. Melancholy and loss, fragility, decay, these are hard to avoid when you look closely at green things. But I don’t think they’re anything to fear. To me, they deepen an experience, rather than sinking it—like when you look at your child laughing and know the time is fleeting. You love harder, not less.

BH: A “scorched-butterfly bruise,” the “fawn-eyed stars,” a whale becoming a “jungle gym for twitchy neon fish” … your imagery is lovely and surprising, and by that I mean you craft such fresh, electric shapes from the everyday materials of living. Can you share a bit about your image-making process?

AA: I try to tune out the noise in my room so I can hear the music down the block. You know how if you’re checking your blood sugar you’re supposed to wipe away the first drop, then test the second? The pure stuff, the reliable stuff, hangs out a little deeper. I do what I can to get at it. The poem “Bear Fight in Rockaway,” for example, is based on a YouTube video of the same name. I spent an absolutely embarrassing amount of time listening to the bears’ guttural combat calls. I wanted to get it right—the judder, the casual ferocity. Growl and groan and snarl and all sorts of other “beary” words presented themselves right away. These were denotatively correct, but they weren’t right in terms of the senses, the body. I had to wipe away those first drops, a process that took less inventiveness than patience.

Other than holding out for precise language, letting stuff get weird is important to me. My mother has synesthesia, so she’ll recite phone numbers and birthdays as these very specific, odd color patterns, like puce-puce-candyapple-sky-chartreuse-indigo-mustard. It’s a trip. A famous composer who had the same so-called “disorder”—a miraculous gift—experienced the sound of D major as “sunlight.” To me, this is the junction of radical and true. I don’t have synesthesia, but I lean on its blurring of the senses when building images. Tastes can be tactile, sounds blend with smells, that kind of thing. It’s not meant to gussy stuff up but to get us closer to full-bodied experience, something rarely limited to one sense. Emerson, of all people, has a poem about this (“Each and All”), the idea that images require a thorough sensory context. Describing fresh-ground black pepper in terms of taste only would be wildly incomplete. Mold wouldn’t be mold without that weird menthol vapor up your nostrils, like a rush of wintergreen. So many sensory collisions.

BH: Motherhood permeates this book. I often find when I write something into a poem (regardless of how confident I feel about the subject—or, actually, especially when I feel confident about the subject!) I learn something new. Do you experience anything similar, and, if so, have you learned anything about motherhood in writing about/to it?

AA: Sequencing the poems taught me a lot: We refer to motherhood as something with a discrete starting point, and clear thematic boundaries, but in organizing the book, I discovered less of a hard line. Poems considering motherhood aren’t, and shouldn’t be, separated from those about violence, or romantic love, or philosophical questions, or political danger. Motherhood intersects these. And many “motherhood” poems aren’t necessarily about motherhood, but about strength, hope, fear, ferocity—they’re just written by mothers, with those topical tools. But, to be sure, all the poems in The Clearing are about risk, and many are about being divided, distracted, kind of two places at once—and those things link up pretty directly to parenthood.

Motherhood has definitely influenced my writing process, and for the better. Being a parent, you’ve got to keep your knees bent—you never know what’s going to break or get poked out or inspire tears/limitless wonder/both. Writing’s like that. You have to be ready for anything, to catch or to push out of the way, to let go of the outline, the plan, if you made one, to make room for babbling, extemporaneous joy.

BH: Often, the speaker of your poems invites the reader to imagine, to speculate, to ask “what if?” Could you speak to the significance of imagination in your work?

AA: The imagination animates everything, guides everything. My daughter and I found a bird’s wing the other day behind our building. No bird, just wing, though we filled in the blanks. Now, we looked at that bird’s wing and touched it and felt wonder at its intricacy, its engineering—that’s real. Observing deeply has value. But part of our response had to do with imagining how the wing came to be, there and detached, and how a simple mesh of feathers can hoist an entire bird into flight—concepts that, though we stood there holding the wing in our hands, were still contingent on the imagination. But aren’t we always imagining? Things go down as anticipated or in unexpected ways. We recognize something we know or sense a disruption, a novelty. These are acts of comparison, and one of the two things being compared always lives in the imagination. Emotionally, too. Justice, injustice, loyalty, disloyalty, for example, are divergences from some opposing, imagined possibility. He didn’t back me up (when he should have). The hunter has a deer in his scope and seems ready to shoot (but might not). Poems bridge the real and the imagined. Often that’s where tension comes from, which is what’s at issue in “If Imagination and Memory Met Unexpectedly, One Last Time.” I like spotlighting that tension, calling it out, showing how memory and imagination are these tight bookends propping up actual experience—sometimes even dictating it—but they never really intersect, like tragic abstract lovers.

BH: How did “The Clearing” become the title poem? Did you know early on that this poem would be a flyer for the event-that-is-the-book, or did the selection happen later on?

AA: Not at all! It was the last decision I made before pressing that “submit” button. The Clearing, originally called Ghost Town, was already in draft form before I even wrote the title poem. In fact it was writing so many poems for the book that led me to a realization about repetitive story structures when it comes to rendering our lives, especially women’s lives. That realization prompted the poem. Right before submitting the manuscript to Milkweed, I suddenly reorganized everything, taking some poems out and adding in others, placing “The Clearing” at the beginning of the book as a kind of statement of purpose, and ultimately changing the book title to reflect that new framing. As soon as I did it, I felt a kind of relief, as if the book weren’t pulling any punches. It was a risk, but one that paid off.