Deep Cuts—Rick Barot's The Galleons

Happy October Milkweed fans and friends! I’d like to introduce the second blog series that I will be curating this year, which we are calling Deep Cuts! In this series I have the privilege of diving in with the author of a compelling Milkweed title and discussing the behind-the-scenes work that goes into the composition and production of their book.

This month, I interviewed the inimitable Rick Barot around his collection of poems The Galleons, forthcoming February 2020. At once intimate and historical, The Galleons articulates both loss and life with always impeccable precision. I’ve been a tremendous fan of Rick’s work as both a poet and a teacher for years so it was an honor to sit a spell with these warm, generous answers on a book I fell head over heels for.

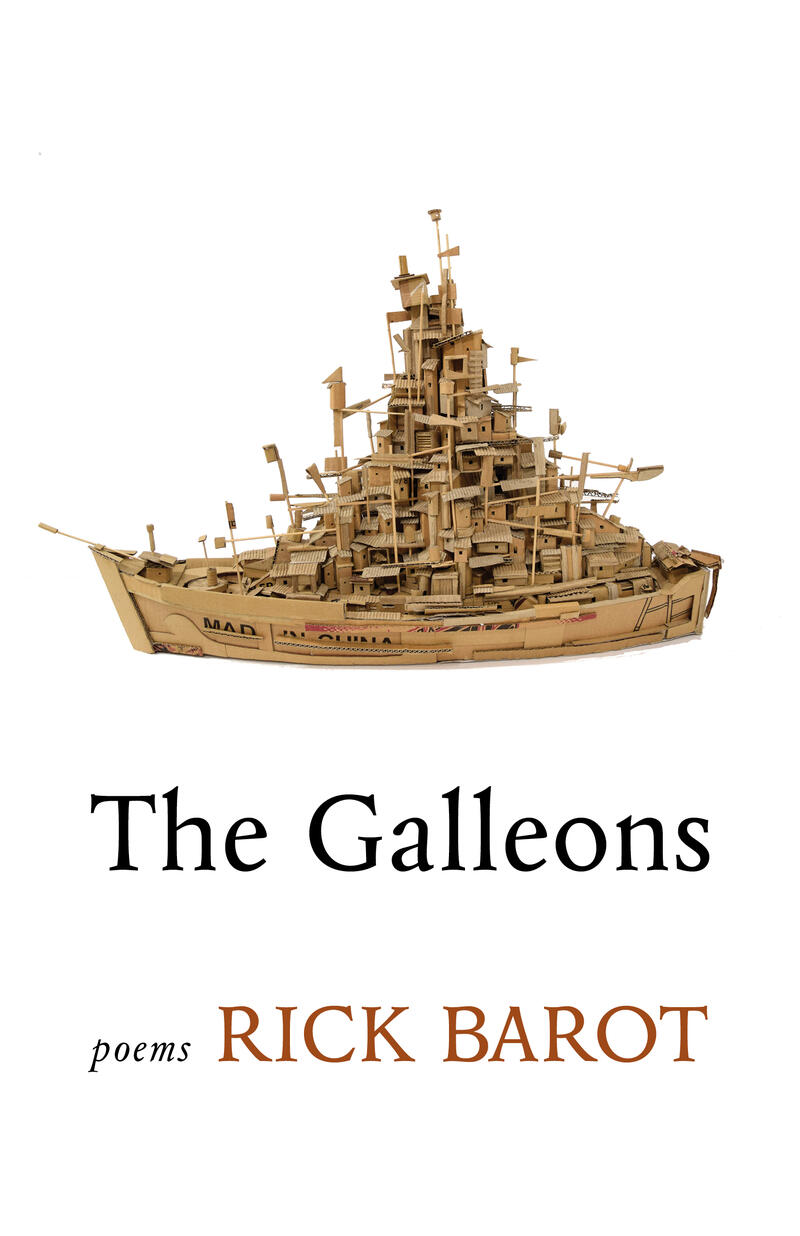

Julian Randall: You’ve long been an incredible ekphrastic poet and I especially admire how in the book’s poem “On Some Items in the Painting by Velazquez” you upend what could be merely a meditation on the decadence of the scene by tracing those items back to their proper places, how they too are reverberations of the colonial theft. Could you tell us more about the book’s cover image, with your admirable eye for visual art, and how it came to be The Galleons’ public face? What feelings and themes do you hope it can convey to a reader encountering the book for the first time?

Rick Barot: I can’t take any of the credit for coming up with the artwork on the cover of The Galleons because it was found by Milkweed’s fabulous art director, Mary Austin Speaker. When Mary sent me the image, I knew immediately that it was the perfect face for the book—a weird, funky, ironic face. Getting to know more about Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan and their incredible work as artists has only confirmed my sense of inevitability for the cover image, which shows a detail from one of their pieces. In their large-scale installations, the Aquilizans, who are Filipinos now based in Australia, bring a kind of material correlative to the things I tried to do in intimate scale in The Galleons—explore experiences of migration and displacement, colonialism and capitalism, personal history and the world-wide Filipino diaspora. There’s also an exuberant inventiveness in their work, which is certainly a quality I hoped to have in my poems. It’s such an honor to have one of the Aquilizans’ images on the cover of The Galleons.

JR: In an interview with The Poet’s Salon earlier this year, you discuss writing poems for “the many constituencies of yourself that are ignored but crying out for poems.” I love this phrase—so many selves to satisfy and there’s something glorious in being fluidly all of them. This is a collection with overtones of Filipino diaspora, loneliness and history and I’m wondering as you were composing it what constituencies within yourself you may have spoken to and written for that surprised you?

RB: In “The Galleons 9,” a poem set in Madrid, there’s a moment when the speaker of the poem overhears two Filipinos talking and this leads to overwhelming emotion in the speaker. The speaker is ostensibly me, and though I don’t specify it in the poem, what I hear is Tagalog being spoken by the Filipinos. Hearing those Filipinos speaking their language so far from home broke something in me, and made me realize how many of us live far away from where we were born. For many of us, home and birthplace and country can mean several different places. Maybe that broken-hearted self in “The Galleons 9” is the constituency I was speaking for in The Galleons. That diasporic self. That self who thinks about his grandmother on a boat crossing the Pacific in the 1940s; who talks to the long-haul truck driver who was a Marine in Afghanistan; and who observes the nannies of New York, many of them from formerly colonized countries.

JR: In “Virginia Woolf’s Walking Stick” there’s this stunning set of lines: “I have come to understand / that the test of how well a thing is made / is to look at the places where its parts come together- / joints, seams, corners, folds. I know it’s a violence to sense and sequence.” Stunning. Just stunning. Throughout this collection there are joints and seams where history, restlessness, and desire occupy the same space. Thinking also of “The Galleons 1” where there is a distinction made between being a part of history and illuminating history, I wonder how your sequencing of this collection navigates this distinction? Is there a somewhat inevitable violence to putting things in order, and if so how did you navigate that here?

RB: In the poems that I’ve been trying to write for a few years now, the violence you’re talking about isn’t just inevitable, it’s in fact the point. When you put seemingly disparate things into the singular space of a poem, what’s generated is tension that the poet has to convert into some kind of harmony. I like seeing things collide in my poems. I like making the mess, and then coming up with the countervailing measure. In the Virginia Woolf poem you refer to, the first half is about Virginia Woolf and the second half is about lost love. The lines that you quote are the hinges that take the reader from one part to the next. A lot of poems in The Galleons depend on those hinges that move each poem from one place to another, one mode of thought to another. Creating all sorts of wild thematic juxtapositions is what I’ve been fascinated by in my work lately. As a result, I’ve also had to think about the craft moves that make those juxtapositions possible—that is, how things like “joints, seams, corners, folds” work.

JR: “The Galleons 6” is a superb poem and to my eye the clear heart of the manuscript and the sequence of “Galleons” poems. In naming each ship chronologically—from the Santiago in 1564 to the Victoria in 1815—the sheer scale of the colonial theft is made starkly clear, to say nothing of the irony of the names (so many saints carrying so many thefts). In many ways it put me in mind of the titular poem of Robin Coste Lewis’ 2015 collection Voyage of The Sable Venus. Especially in a sequence of poems that, aside from numerical distinctions, share the same name, there’s a deep power in the precision of naming. What was the composition of this poem like? I’m especially fascinated by where it fell in the overall composition of the manuscript.

RB: In 2016, I went to Madrid for the first time. Coincidentally, the Royal Naval Museum had a lavish exhibition celebrating the 250 years of the Spanish galleon trade in the Pacific. There were rooms highlighting the arduous route, the technologies needed to make the journeys, and the cargoes of the ships. The exhibition was meant to present a triumphalist narrative, which was understandable, given the venue. For me, walking through the exhibition was thrilling and melancholic at the same. At the entrance to the exhibit was a map that listed the 200 or so ships that naval historians have identified as having participated in the galleon trade. In a sort of frenzy, I wrote down all the ships’ names and their launch dates, not knowing what I’d do with the list. Taking the names down felt like a sweet theft of its own. Later on, when I was deep in the work of writing the “Galleons” sequence, I realized that presenting the list as it was would give the sequence a dark gravity, and so I went for it, even though the list was about 10 pages long in manuscript. In the book, “The Galleons 6” is followed immediately by “The Galleons 7,” a four-line poem that evokes my grandmother’s death. That juxtaposition of two incongruous scales—the grandeur of the ship catalogue and the intimacy of my grandmother’s death—feels like the heart of The Galleons to me.

JR: Unless I’m mistaken I believe that this whole collection is done in couplets, which I love. What I see the couplets doing is conveying a parallelism, of bodies and histories, and in the case of “The Galleons 5” a parallel of voice. There’s an intimacy to that which I admire immensely. What was the intent behind this choice?

RB: When I started writing the poems for The Galleons, I was coming out of a period of two years when I didn’t write poems. The only way I could trick myself into thinking that I wasn’t writing poems—which had become so high-stakes for me at that point—was to write all my first drafts in prose, which seemed to turn off the part of my brain that was anxious about the act of writing poems. In the next round of work on each poem, I would break down the prose block into stanzas. Because the prose blocks were so dense on the page, my initial response was to put the next draft into couplets—something with space and air. I put all the poems into couplets, thinking that maybe I would make other decisions about their stanzas later on. At some point, though, I realized that I loved the couplets and didn’t want the poems to be in other shapes on the page. It’s also probably worth mentioning that around this time I was having an intense engagement with the work of Agnes Martin. All the grids and vertical and horizontal lines in her work—a whole obsessive vocabulary. That was in my head, and it seemed like permission to commit to the couplets in my poems.