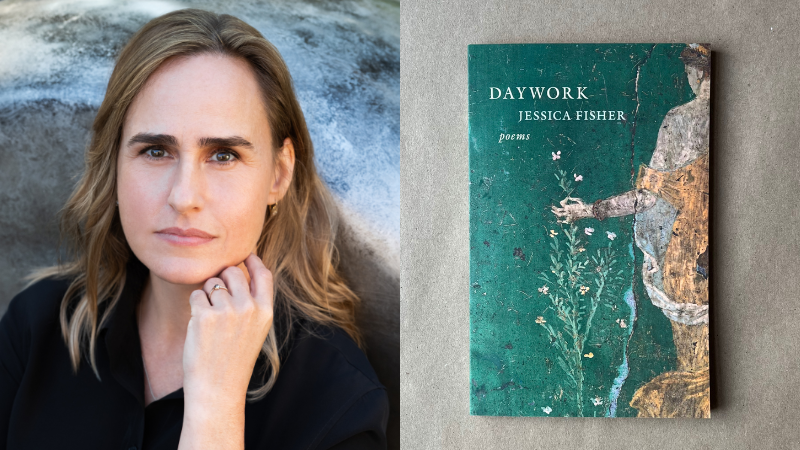

Four questions with Daywork author Jessica Fisher

How do artists work within constrictions of time? How can our existence be traced through art? How does writing ekphrastic poetry compare with linguistic translation? How is historical time considered with care in stretching both towards the past and into the future? These are some of the questions poet Jessica Fisher unpacks with her work in Daywork and in our Q&A below!

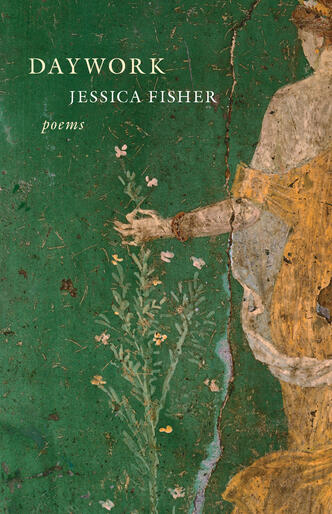

Milkweed Staff: Daywork takes its title from the giornata—the term in fresco painting for the section of wet plaster that can be painted in a single day. When did you first discover this concept? And what prompted you to use it as one of the central themes of this collection?

Jessica Fisher: I began to think about the giornata during the year I spent as a fellow at the American Academy in Rome.

It came to be a resonant concept for me because of the way it brings together two very different temporalities: the relation of lived time and the long duration of art.

Once, a great painter would take pains to hide the limitations of the day, to make the work feel seamless; still, behind even the most monumental works of art, there is some trace of a human body working in time.

This focus came in part from my own desire to bring together my life and my art. My children were very young, and my second book, Inmost, had just come out, when I had an encounter that really affected me: a famous writer whom I met at the Academy told me that I wouldn’t have the solitude and depth of thought necessary to write poetry for a long time, given the many distractions that my life as a mother and new assistant professor guaranteed me. What he said would have hurt me if I didn’t realize in the moment that what differed between us was not so much the conditions of our lives, but what we imagined art to be, both as subject and as form.

I realized that the aesthetics of the contemporary artists that interest me has much more to do with the revelation of process and with the active transformation of material.

MS: You’re also a translator who is fluent in both French and German. How would you compare and contrast the processes of translating across languages to translating across mediums, as is central to the composition of ekphrastic poetry?

JF: I think that in one sense, all art is a form of translation, whereby perception, emotion, and imagination find their way into form; the work of translation is perhaps just more readily apparent in interlingual translation and in the ekphrastic poem. As I see it, the task of the translator is not to try to make an equivalent version of the original object, but to enter into the energetic field of another person’s making, and to be transformed by it, to speak from it.

Ekphrasis has interested me for a long time—it was even the subject of my senior thesis in college—but by now, I have lived with and through visual art for so long that it is just one of the many “things / we live among,” in the words of the inimitable George Oppen, “and to see them / is to know ourselves.” And yet that knowing is full of alterity—“Je est un autre” (“I is an other”), as Arthur Rimbaud put it. Or, to quote Czesław Miłosz, one of the poets I first translated, and for whom I served as assistant in his last years,

The purpose of poetry is to remind us

how difficult it is to remain just one person,

for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors,

and invisible guests come in and out at will.

Here, Miłosz captures one aspect of writing that I find hard to describe—that when I write, something speaks that is beyond just me. This remains for me one of the great mysteries of lyric voice, and why I remain so interested in it.

MS: How did your background in art history studies influence the creation and revision of these poems?

JF: I began this book over a decade ago, while I was living with my family in Rome. Before that period in my life, I knew little about antiquity, and I was inspired to greatly expand my knowledge of art history beyond the modern and contemporary work I’d studied in school. I was particularly interested in spending time with the site-specific works of makers like Michelangelo, Raphael, and Caravaggio, as well as of earlier makers. Equally crucial, though, were certain archaeological sites—a columbarium accessed through a narrow underground stairway in a local park, for example, or Mithraic sites beneath extant churches, or the hill of potsherds in Testaccio—where I found a different sort of vestige.

But the lessons of Rome, where violence and beauty are inextricable, are also difficult ones.

In thinking about the residue of the past, I was also thinking of what our present moment will leave in its trace, and was grieving the fact of our species’s long history of destruction.

I was aware, too, of an imminent personal loss, since my friend, the remarkable poet Hillary Gravendyk, was dying. Death seemed to me another form of translation: How to imagine carrying the conversation with her past the limit of her life? This became one of the many questions the book went on to explore over its long gestation.

MS: Since the publication of your last collection of poems, has your process for writing poetry changed or evolved in any way? What were some of the larger, more existential questions you were preoccupied with then versus now?

JF: I wrote Inmost during my children’s infancy and early years, and during the United States’ war on Iraq. The book considers the relation of creation and destruction, nurture and violence, often seeing them as two sides of the same coin. It also investigates the concept of mirroring: of the intimacy between generations, and the successive separations of mother and child. Ultimately, Inmost suggests that no matter how distant our wars, the culpability and violence of war are, like the child, “inmost.”

Daywork, by contrast, considers how one comes to understand historical time, which stretches not only into the past, but also into the future. And yet these distant horizons can only be perceived from the vantage of the present moment, from our own embodied beings.

I knew from early on that these poems were compelled to bring “the faraway … close”; what I couldn’t foresee was the past decade’s rapid acceleration of violence and isolation, and the resulting way that even aspects of the present have come to feel distant. Of course, extending our care into the historical past, and into the nebulous future, remains as difficult a challenge as it ever was. Even so, I am more convinced than ever of its importance and of the necessity of the imagination in achieving it.