Listen Here: National Poetry Month Special (Part One)

Hello, friends! Welcome to a very special edition of 5 Reasons to Teach This Book. This month, we’re taking a break from our standard five-question, solo-author interview format; instead, we’re taking a stroll with a few different poets through new books and returning favorites in Milkweed’s 2021 poetry lineup. And oh, hey, look at that—it’s National Poetry Month! Why not celebrate by listening to each of these striking poets read from their collections?

We’re starting off this two-part feature with Wayne Miller, Kathryn Smith, and Robert VanderMolen, each of whom have new books out now (or soon!) with Milkweed. Each collection has its own pulse and its own fixations, from climate catastrophe to aging to the prevailing interconectedness of our daily lives. Starstruck by their work, I found I wanted to know more about each of these distinct poets’ bookmaking process—read on to see (and hear) more!

Note: for best listening experience, please use Google Chrome.

“Carillon” and “Generational” from We the Jury

Bailey Hutchinson: I often think—both as a writer and as a reader—about the “project” of a poetry collection. For some it seems like the shape of a book becomes slowly visible in a body of work—like a facial feature we didn’t clock until we spent a long time looking in the mirror. But sometimes the idea of the book exists long before the poems that make it. Which was the case for you?

Wayne Miller: I wrote the poems in We the Jury between 2015 and 2019. For the first two years of writing I didn’t know what shape the book would take—I was just writing poems. But in maybe 2018, when I gathered what I’d written up to that point, it became clear that there were emerging themes: violence, middle age, death and illness, American social fragmentation, the importance of humanism.

At that point I began “writing into the book,” trying to add poems that would help make the collection feel more unified and balanced. For example, I wrote a second long poem, “On History,” as a companion to the early long poem “On Progress.” And the title poem came late; it imagines a jury asked to pass judgment on itself, and it helped, I think, to pull together the book’s themes under one larger idea.

It’s also true that, while We the Jury isn’t really a “project” book, I, like all poets, have my ongoing artistic and intellectual interests. For some time I’ve been trying to think in my poems about the connections (and disconnects) between small, domestic narratives and large, soiciohistorical metanarratives. The poems in We the Jury range in subjects from a miscarriage and the death of a sister to the Great Recession and the decline of the American middle class. Juxtaposing poems of significantly different scopes is, for me, an abstract and ongoing kind of “project.”

BH: Some (okay, it’s me, I’m “some”) would say that teaching poetry-reading (as in, reading a poem out loud) is as important as teaching poetry-writing (as in, committing words to the page). And some might also say there’s a distinct power in poetry as an audible experience. This is a long way to ask: what goodness does hearing poetry carry for us, right now?

WM: Performing a poem out loud isn’t easy. I think a poem is read well if it helps me hear something of the author’s true voice—the author’s sonic intent. That means that not all poets—or even poems by one poet—should sound exactly the same when they’re performed. More than anything else, I want to come away from hearing a poem having learned something about it—its pacing, its sense of voice and form, its subtle shifts of register—that I can carry forward with me to when I read it on my own. When a poem is performed well (by the author or not), the poem becomes enlarged and focused.

But if I’m hearing your question right, you’re also asking about the benefit of performing poems right now, after a year of Covid lockdowns and isolation. For me, reading and hearing a poem out loud alongside other people turns the poem into a kind of room that we inhabit together (even if we’re all in separate rooms). All of our minds are, however briefly, in the same space at the same time—and in this time of division and isolation we could certainly use more of that.

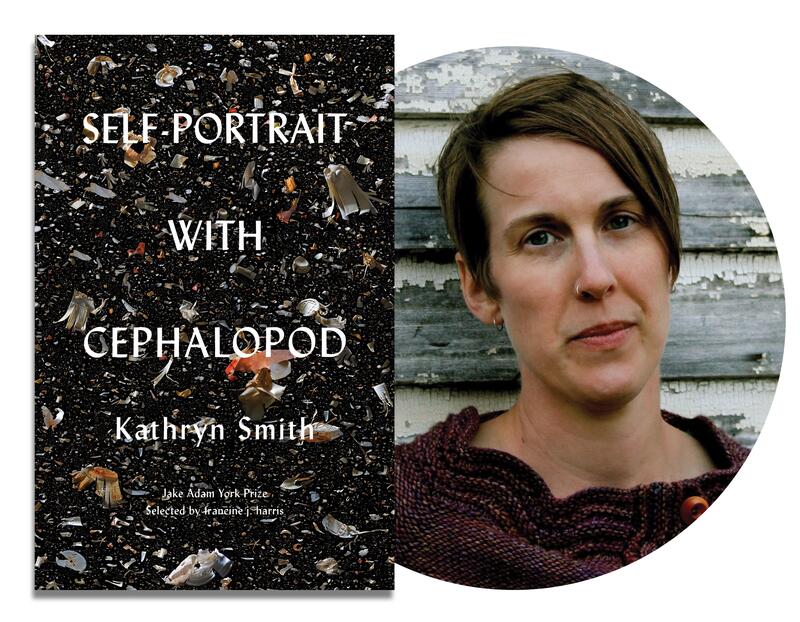

“Dear Sirs,” and “The Windows Kept On,” from Self-Portrait with Cephalopod

Bailey Hutchinson: Sometimes the idea of the book exists long before the poems that make it. Which was the case for you?

Kathryn Smith: Definitely the former. The poems in Self-Portrait with Cephalopod were written over a span of several years, so as I brought the poems together into a collection, it took some time to see the threads that held them together. I like the analogy of the facial feature, because I think the idea of maturity comes into it as well—the way we sometimes have to grow into our features. The earlier poems needed to wait until the later poems had been written to fully come into their own as part of a collection, I think. And the later poems need the earlier ones to give the book context and depth.

The theme of climate change—or climate dread as I’ve come to think of it—is one of the most persistent, even if it isn’t always the most dominant. So even as the poems shift between hope and hopelessness, as they look inward toward personal history and reach outward toward science and myth and the wider world, there’s always the backdrop (or sometimes foreground) of environmental collapse—of living, as the first poem puts it, “on a planet poised for disaster.” But I didn’t know that was happening until the poems told me.

BH: What goodness does hearing poetry carry for us, right now?

KS: I think anyone who watched Amanda Gorman’s performance at the Inauguration can tell you how hearing poetry can do a world of good right now. So many people, regardless of their previous experience with poetry, felt moved and uplifted hearing Gorman’s poem. It made people aware of poetry’s potential–even people who would have told you that they’re not into poetry.

There’s also something immensely powerful about poetry as a communal experience–about hearing that poem at the same time as millions of others, even though most of us experienced it in a socially distanced way. Of course, these communal experiences rarely happen on such a large scale. But smaller-scale events can have a meaningful impact, too.

I launched Self-Portrait with Cephalopod with a virtual reading, which gave me the opportunity to share the stage with three of my best poet-friends. I’ve been writing with these friends for a number of years, and our poems are often in conversation with each other. I wanted my reading to celebrate this community, and to let others in on our poetic conversations. We were able to read our poems to each other, and the audience was able to hear not just the poems, but where they intersect. If someone were to encounter those same poems on the page, I’m sure they would see the same connections, but hearing them draws attention to the community aspect, I think. It makes the connections between the poems feel like connections between humans.

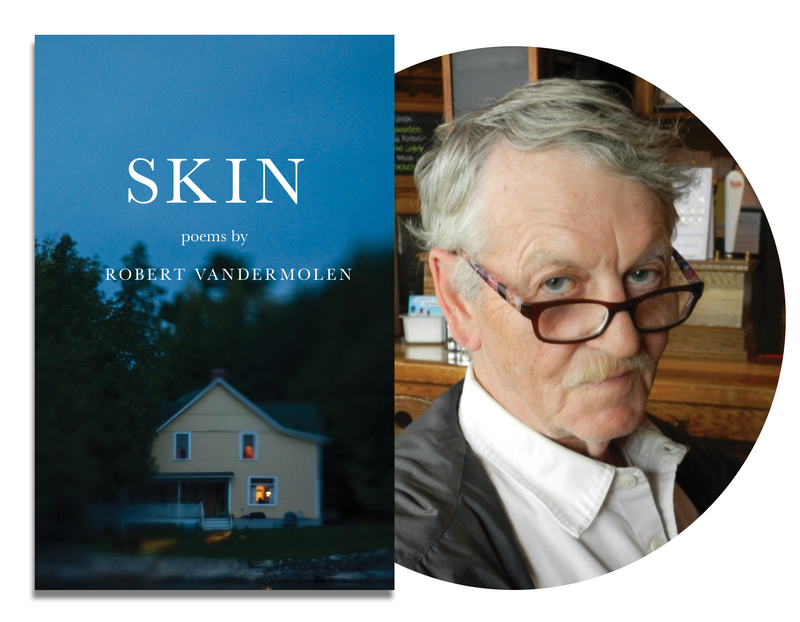

“Indoor Plants” and “The Clouds” from Skin

Bailey Hutchinson: Sometimes the idea of the book exists long before the poems that make it. Which was the case for you?

Robert VanderMolen: I never start with a concept of a book. Instead, I let the poems pile up until it appears I have a great many. Then I figure out a title and try to arrange them in some kind of order—which I’m not terribly successful at doing (I have too great an investment in each piece, it skews the process). Generally an editor rearranges everything in a way I never could—which amazes me. (No doubt I’m not editor material.) What interests me is writing. I suppose I’m addicted to it. I started seriously when I was 15 years old (in the back of French class—which I nearly flunked). I write nearly every day or I take notes. If writing ever becomes unenjoyable for me I’ll quit.