Wayne Miller’s books of poetry include Only the Senses Sleep, The Book of Props, The City, Our City, Post-, and We the Jury. His awards include a William Carlos Williams Award, two Colorado Book Awards, an NEA Translation Fellowship, six individual awards from the Poetry Society of America, and a Fulbright Distinguished Scholarship to Northern Ireland. He has co-translated two books from Albanian—most recently Moikom Zeqo’s Zodiac, shortlisted for the PEN Center USA Award in Translation—and has co-edited three books, most recently Literary Publishing in the Twenty-First Century. He lives in Denver, where he co-directs the Unsung Masters Series, teaches at the University of Colorado Denver, and edits Copper Nickel.

Like this author? Sign up for occasional updates

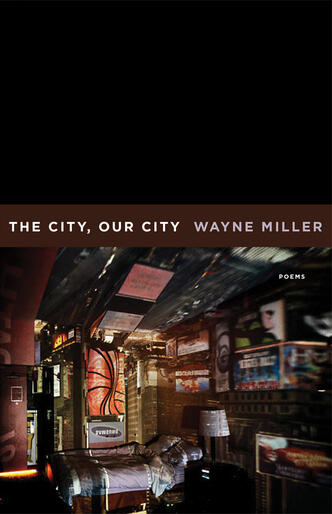

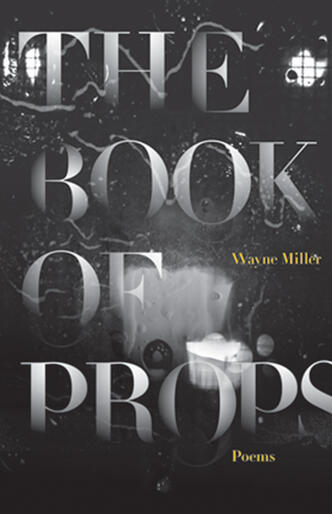

Books by Wayne Miller

A tender and provocative collection of poems interrogating the troubles and wonders of both childhood and parenthood against the backdrop of global violence.

A boy asks his father what it means to die; a poet wonders whether we can truly know another’s thoughts; a man tries to understand how extreme violence and grace can occupy the same space. These are the questions tackled in these poems.

Bringing together a wide range of perspectives—industry veterans and provocateurs, writers, editors, and digital mavericks—this collection reflects on the current situation of literary publishing, and provides a road map for the shifting geography of its future.

These poems exist in the wake of catastrophe: rogue gunmen, debt, hoax bombs, riots, and consumerism all haunt its pages. And yet this collection cuts through pain to open up a way forward, thrumming with pathos and humor, pain and the beauty of living.

A breakout collection that showcases the voice of a young poet striking out, dramatically, emphatically, to stake his claim on “the City”—an unnamed, crowded place. These poems—in turn elegiac, celebratory, haunting, grave, and joyful—give hum to our modern experience, to all those caught up in the City’s immensity.

A tightrope walker who travels on telephone wires; angels, scarecrows, friends, and lovers—the speakers in these poems often desire to hold time still, even as they acknowledge that to do so would actually mean the death of love, of experience. This collection is an imaginative yet authentic inquiry into the varied constructs in which we define love.

Related Media

Author Q & A

- Question

Do you believe in inspiration? How much of this poem was “received” and how much was the result of sweat and tears?

Brian Brodeur, How a Poem HappensAnswerI like William Stafford’s idea about this. I’m paraphrasing, but he says something like: a poet is someone who has arrived at a method that allows him to say things he could not have said without that method. My method is nothing like Stafford’s (he wrote a poem every day before getting out of bed—and when a poem didn’t come, he would “lower his standards”), but I do think it’s the consistent work of continually touching back in with the possibility of a poem—and then, once I have a draft, with the poem-in-progress—that allows me to arrive at moments of genuine surprise. Moments, in other words, that feel “received” somehow. [Read more at How a Poem Happens]

- Question

How long do you let a poem “sit” before you send it off into the world? Do you have any rules about this or does your practice vary with every poem?

Brian Brodeur, How a Poem HappensAnswerI think what I outline above is typical: I carry a poem around and read it over obsessively, tinkering, revising, etc., until I exhaust myself and put it away for a couple weeks. Then I touch back in with it. If it seems done at that point—when I no longer quite remember the particular details of writing it—I send it out. If the poem requires more revision, I continue revising, then put it away again. Rinse, wash repeat. Sometimes after one of those repetitions I just abandon the poem. Other times, I find it’s done and I put it in the mail. If it comes back rejected, I check back in with it to see if I need to revise further. [Read more at How a Poem Happens]

- Question

Do you have any particular audience in mind when you write, an ideal reader?

Brian Brodeur, How a Poem HappensAnswerI tend to imagine a future audience—some person fifty or one hundred years from now who’s literate and has read a decent range of poetry. I’m by no means so confident in my work to be convinced I’ll be read in the future (are any poets so sure of themselves?), but I think it’s important—at least for me—to write with such an audience in mind. I try to remember that an important part of why we read poetry is to connect intimately with a mind that’s not our own—to discover as directly as possible how a mind in a different time or location lived and experienced the world around itself. When I’m thinking about the relative value (or non-value) of a poem of mine, I sometimes consider how well it some aspect our own moment in history—or at least of my tiny slice of it. [Read more at How a Poem Happens]

You Might Enjoy

Listen Here: National Poetry Month Special (Part One)

Hello, friends! Welcome to a very special edition of 5 Reasons to Teach This Book. This month, we’re taking…

In Person: Angela Pelster at A Room of One's Own

Join Angela Pelster at A Room of One’s Own for a reading and discussion of her latest work, The Evolution…