Once You’ve Seen into Heaven, How Do You Forget That? On the Opioid Epidemic and I Know Your Kind

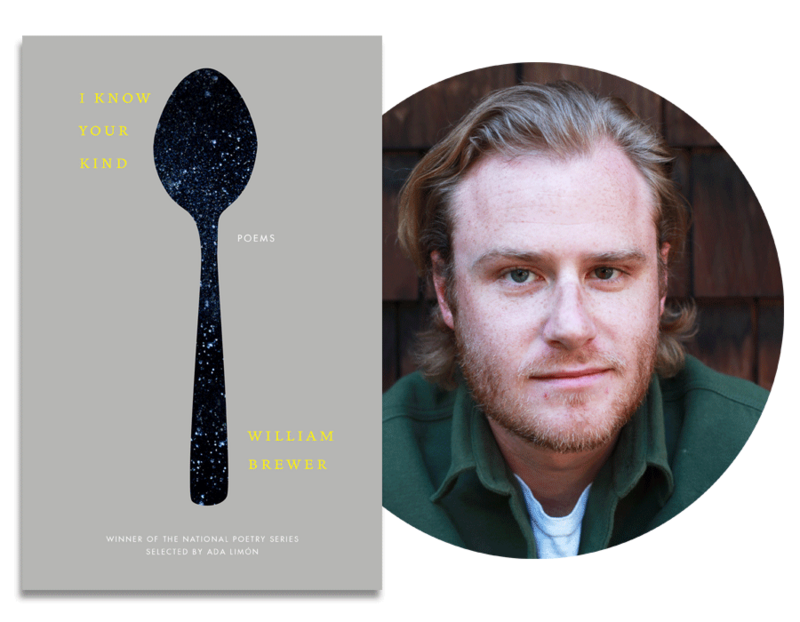

Editor’s Note: Selected for the National Poetry Series by Ada Limón, I Know Your Kind is William Brewer’s debut collection, about the American opioid epidemic and poverty in rural Appalachia. Here, Brewer describes what motivated the project.

I saw the opiate epidemic start to swallow up my home. It worked quickly and indiscriminately. Each trip back was met with news of a different friend using, or in rehab, or dealing, or in jail, or worse. But it was only after a very specific moment that I became committed to writing this book, a moment of initial frustration within myself. Someone came to me and my partner and admitted they were a heroin addict (their using began with pills). I was extremely angry with them and brushed them off, saying things like forget about them, they didn’t consider other people or their family, they put themselves in that position. Very quickly after that, by which I mean within a matter of minutes, I was overwhelmed with repulsion toward myself for how quickly I had slipped into such a damning, limited, and unsophisticated view of what this person had just confessed. Here they were, at their most vulnerable, and I couldn’t be less humane. It occurred to me that, if I—someone who likes to think of themselves as a writer, which in my case means spending 99% of my time trying to imagine and understand the nuances of others’ experiences—am this susceptible to such a foolish, inhumane way of reacting to a problem, I was inclined to think the average response couldn’t be much better, and that to me was terrifying. I decided it was something I should push against by making a piece of art that instead argues for the humanity of the people dealing with this epidemic and that creates a space for all those connected to it.

Above all, these poems strive to empathize with those struggling with addiction and to counter our nation’s instinct to stigmatize and punish. I hope that my poems read as an extended elegy for the people and places that have been lost to opiates.

My junior year of college I slipped on some black ice and snapped my right shin in half. The pain was indescribable, so much so I went white blind. At the hospital, the doctors shot me twice in the butt with sizeable vials of morphine. I can still remember, with vivid adoration, the power of those opiates. One moment I was deep in the fiery isolation of pain, the next I was peering through a hole in the wall around heaven. And that’s one of the central questions that is unique to these drugs and this problem. Once you’ve seen into heaven, how do you forget that? And then how do you forget that when you live in a place as poor and ravaged as West Virginia, a place most of the country wants to forget about, if it hasn’t already.

In short, the book came out of a need to understand, communicate, and connect. The poems are for those trying to make sense of it all. The Appalachian landscape, with its stark contrasts of beauty and ruin, nature and industry, functions as both a mirror for the physical and psychological extremes caused by these drugs, as well as a stage upon which these dramas unfold. I hope these poems also resonate on a national level, as the opiate epidemic continues to spread, bringing all of its cultural, philosophical, and spiritual problems with it. And while there may be no clear conclusions, I hope that, at the very least, the reader will feel less alone in their search for answers.

EXPLANATION OF MATTER IN OXYANA

from I Know Your Kind

At Crockett’s bar, the last of the old glassblowers,

drunk, his sand-filled lungs

telling time, says I’m wrong

about the laws of the universe.

Fire isn’t matter. It’s plasma.

It’s process—flame and light …

What about that white glow,

both energy and brilliance,

deep in the furnaces you blew in, I ask.

That, he says, that’s becoming—

I ask what became of you, I say your name, he says we hold only empty names.

I tell him how the night you died

I ran into the yard, shoved snow in my mouth, and screamed your name,

the steam braiding out like when some forged thing

is quenched in a slack tub,

metal hardened, beaten

to its final purpose, I swear something iron

fell from my tongue …

He says the heart (factory of blood) is iron,

names are only ever glass.