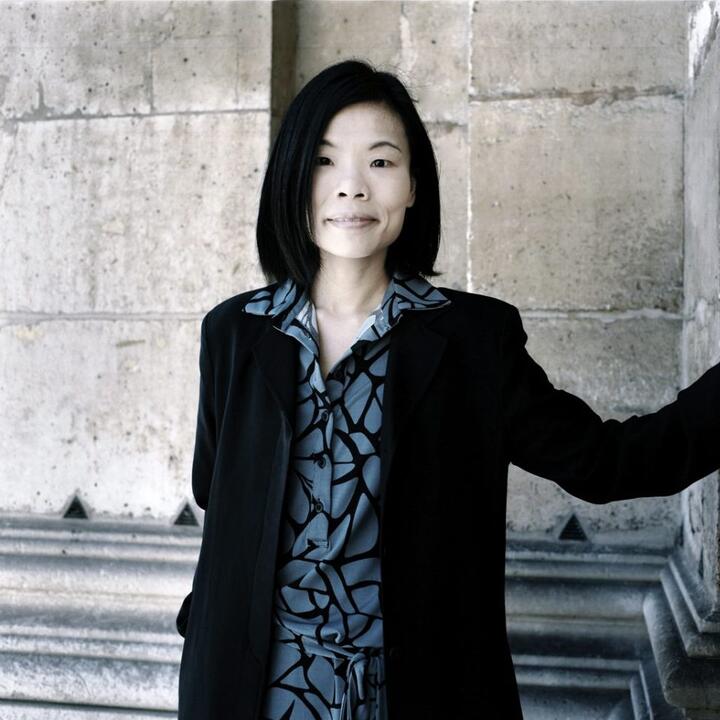

Fiona Sze-Lorrain

Fiona Sze-Lorrain writes and translates in English, French, and Chinese. Most recently, she is the translator of Yi Lu’s Sea Summit, a finalist for the Best Translated Book Award in 2016. Sze-Lorrain is also the author of The Ruined Elegance, a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Poetry, as well as My Funeral Gondola and Water the Moon. An editor at Cerise Press and co-director of Vif Éditions, an independent French publishing house in Paris, Sze-Lorrain is also an acclaimed zheng harpist.

Like this author? Sign up for occasional updates

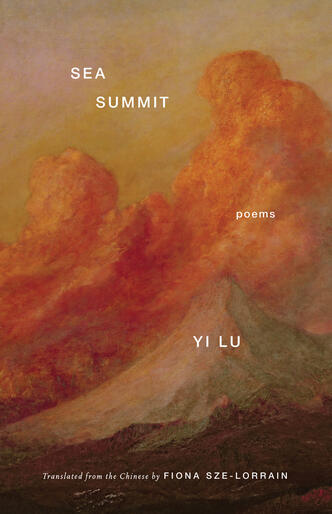

Books by Fiona Sze-Lorrain

Books translated by Fiona Sze-Lorrain

The sea is an impossible force in this collection: it is both a majestic presence that predates man, and something to carry with us wherever we go. These brilliantly translated poems, presented in both Chinese and English, introduce an important contemporary Chinese poet to American readers.

Author Q & A

- Question

How do you see yourself as an artist—as a poet, translator, and musician?

Lantern ReviewAnswerTranslation is a meaningful form of resistance: beyond the necessary literary challenges, the experience of living with the work—during and after the translation process—[it] is a test of harmony between my own poems and the engagement of the other. I think of a poem as a secret about a secret, to paraphrase Diane Arbus. In this sense, the act of translating a poem legitimizes a zone where secrets are mobile, and [are] made more present without being visible. I don’t have a specific writing ritual. The same goes for translation. However, I need to work in a room and alone. It seems possible for me to write poems while translating on the side, but not vice versa. I try to honor the experience as best as the work allows. I listen to music to ease the transition from one to the other. [Read more at Lantern Review]

- Question

Tell me about your poetic influences.

Christina Cook, TriQuarterlyAnswerI am embarrassed to confess that I read more prose and plays—probably music, too—than poetry. I read Proust every year and am still reading the same Bach sinfonias as when I was nine. Preferences also include various translations of Buddhist scriptures and Latin texts. I recently read Hammarskjöld (in Auden’s translation) and Elfriede Jelinek’s Princess Plays. (Jackie, which is part of Jelinek’s Princess Plays, was on show at Théâtre Gérald-Philipe this April. It is now playing off-Broadway in New York, as a Women’s Project production.) But to answer your question, here are some of my poetic likes: Bashō, Milosz, Lorca, Miron Białoszewski, Eugenio Montale, Emily Dickinson, Tao Yuanming …

[Read more on TriQuarterly]

- Question

Are there Chinese, French, and English/American poets who have influenced you?

Christina Cook, TriQuarterlyAnswerOther than the ones mentioned above—Joan Mitchell. She is a painter, but her work taught me how to approach writing as an expression and a form of expressiveness. Her paintings introduce me to colors, the outbursts of energy and stilled visual scenes in poetry from a different dynamics. So much passion and sincerity lives in her art. I like poetry that isn’t a mental conception or “something that just takes place in the head.” Perhaps my failing—but I can’t believe in “imagination” when it happens as a choice of nonengagement with experience or the real. It is a question of ethics. The real has nothing to do with the limits of autobiography, but the unreal—surprise!—can be a manifestation of autobiographical maskings. Poetic imagination seems to travel further when it is a search, as opposed to being a result. Not the absolute truth but a practice in truthfulness. Please do not accept these as facts. They are just my thoughts, a work in progress. In French literature, I revisit Rimbaud and Victor Hugo. They are my literary heroes. They write the way they live—not the other way round. [Read more at TriQuarterly]

You Might Enjoy

A War on All Fronts: Chris Santiago’s Small Wars Manual, the Future of Poetry, and the Casualties of A.I.

As we pass the perihelion of National Poetry Month, Milkweed Editions celebrated the launch of Chris Santiago’s newest poetry collection, …

Virtual: Karen Babine at Terrain.org Reading

Join Karen Babine for the virtual Terrain.org reading alongside Elizabeth Jacobson and Ian Ramsey. The reading will be followed by…